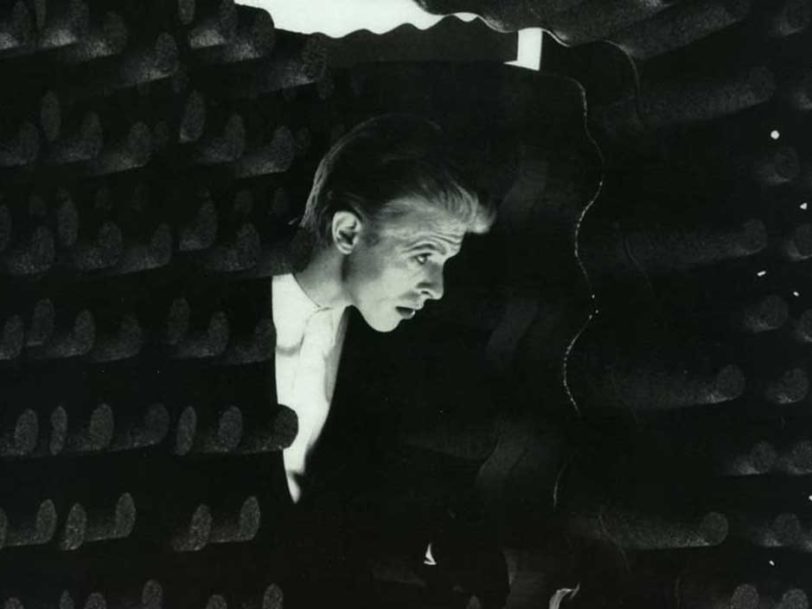

Half a decade after writing himself into fame with the intergalactic rock messiah Ziggy Stardust, David Bowie was in danger of crash-landing – just like Thomas Jerome Newton, the extraterrestrial he had assumed the role of throughout August 1975 in Nicolas Roeg’s film adaptation of Walter Tevis’ sci-fi novel, The Man Who Fell To Earth. Though he looked healthier than he had in a while during the shoot, which took place in New Mexico, and for which Bowie, in deference to the demands of the movie, resolved to lead a clean life, when he returned to Los Angeles, preparing to work on what would become his new album, Station To Station, Bowie was at a spiritual, psychological and artistic crossroads that would eventually lead to one of his greatest albums – but not before a reckoning with himself, and with what he called “demons of the future on the battlegrounds of one’s emotional plane”.

Listen to Station To Station here.

“I was out of my mind, completely crazed”

Where Philadelphia soul had influenced the sound and style of his previous album, Young Americans, The City Of Angels now had Bowie in a malign grip. “Los Angeles, that’s where it all happened,” he later told the NME. “The fucking place should be wiped off the Earth.”

“It all” was not only the Station To Station recording sessions, which took place from September through November 1975 in Hollywood’s Cherokee Recording Studios – chosen by co-producer Harry Maslin for the relative anonymity it afforded them compared to higher-profile facilities such as Sunset Sound and Capitol Studios – but the lifestyle that led Bowie to the personal crisis he sought to resolve on the album.

“It was a dangerous time. I was doing too much, with too small a handful of what one might call real friends,” Bowie admitted to journalist Cameron Crowe. He’d not been alone in embracing the excesses available to a global rock star in the mid-70s, but the psychological fall-out that seemed to be coming would frame Station To Station and, ultimately, lead Bowie into entirely new phases, both personally and creatively.

“It’s a blur, topped off with chronic anxiety”

“I had this more-than-passing interest in Egyptology, mysticism, the Kabbalah, all this stuff that is inherently misleading in life,” Bowie recalled in 1983. Black magic, Aleister Crowley’s late-19th-century collection of occultist poetry, White Stains, and the Stations Of The Cross also filled his head. Pushing himself to extremes, Bowie kept increasingly long hours (“There’s things that you have to do to stay up that long,” he later acknowledged) that would see him enter a “hallucinogenic state” in which he envisioned “this bizarre nihilistic fantasy world of oncoming doom, mythological characters and imminent totalitarianism”. To Crowe, he reported seeing a body fall past his apartment window, so had taken to living with the blinds drawn, lighting black candles and scrawling chalk symbols around the place, in the hopes of warding off evil spirits.

“It’s a blur, topped off with chronic anxiety, bordering on paranoia,” Bowie said of what was “probably one of the worst periods of my life”.

Though Bowie’s instinct for a headline-grabbing interview could conceivably have led to embellishments for the press, in the years that followed he always insisted he’d been “out of my mind, completely crazed” during the Station To Station sessions. In retrospect, Bowie would come to see the album as “a plea to come back to Europe for me… one of those self-chat things one has with oneself from time to time”, but he also claimed not to remember the sessions that produced it (“I know it was recorded in LA, because I read that it was,” he joked).

“I’ve rocked my roll”

To outsiders, Bowie seemed to be working on a natural follow-up to Young Americans. Knocked off quickly, and issued as a single in November 1975, Golden Years was an assured piece of catchy funk that went Top 10 on both sides of the Atlantic and, along with Young Americans’ Fame, earned Bowie a performance on Soul Train, making him one of the first white musicians to appear on Don Cornelius’ iconic TV show. As sessions for Station To Station unfolded, however, it became clear that Bowie was pursuing an entirely different vision, and was spending more time than ever in the studio trying to capture it.