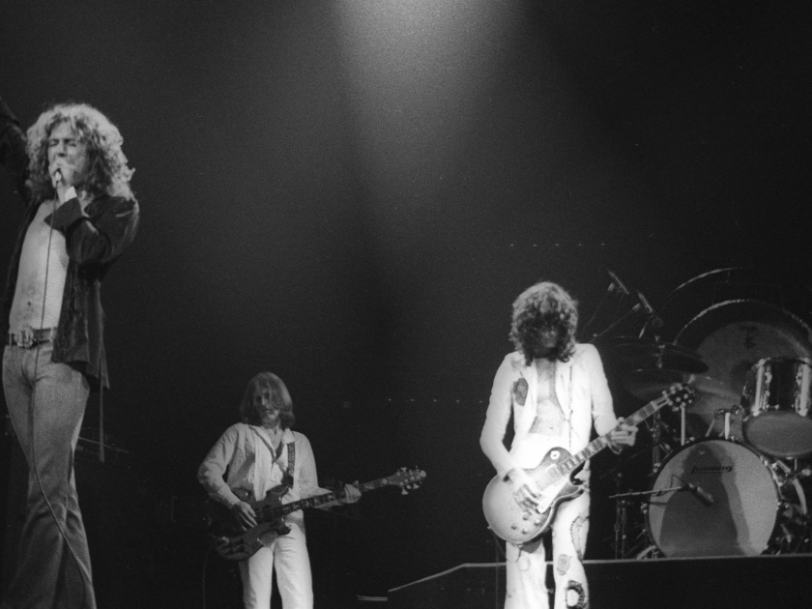

After The Beatles threw down the gauntlet with “The White Album”, every rock band worth their salt decided they should record a sprawling double album – at least until punk came along and turned rock’s established tropes on their head. By then, of course, Led Zeppelin had already weighed in with 1975’s Physical Graffiti: a monolithic, chart-topping double-disc set fully deserving of the term “magnum opus”. Its majestic centrepiece, Kashmir, generally gathers the plaudits, but as this track-by-track guide to each of its 15 songs reveals, Physical Graffiti still sprays brilliance all over the shop.

Listen to ‘Physical Graffiti’ here.

‘Physical Graffiti’: A Track-By-Track Guide To Every Song On The Album

Custard Pie

Physical Graffiti starts off as it means to go on with Custard Pie: a feisty, flab-free rocker clocking in at just over four minutes in length. Culled from Led Zeppelin’s highly fruitful sessions at Headley Grange, a former workhouse turned recording studio in rural Hampshire, in early 1974, this spirited set-piece captures the entire quartet on fine form, with the standard rock-group instrumentation augmented by Robert Plant’s wailing harmonica and John Paul Jones’ snaky Clavinet. It remains fresh and zesty to this day.