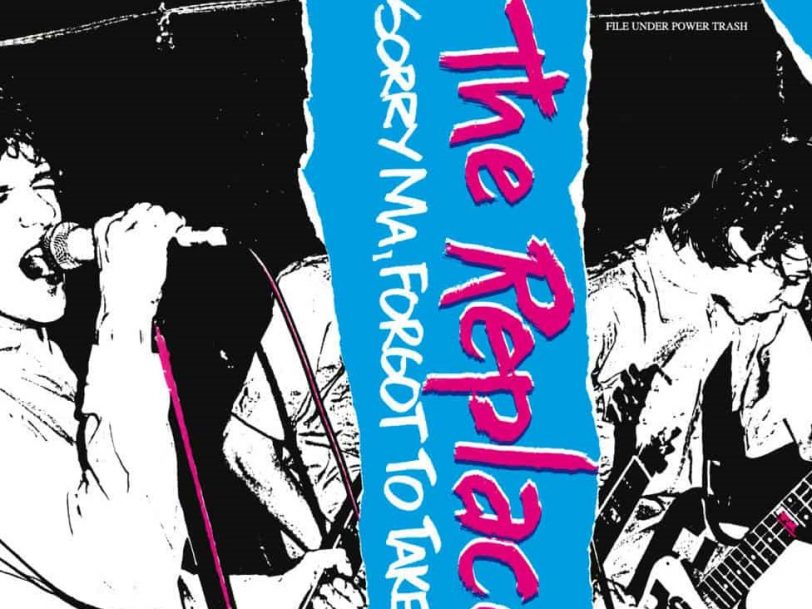

Released in the summer of August 1981, The Replacements’ debut album, Sorry Ma, Forgot To Take Out The Trash, immediately set the Minneapolis four-piece apart on the US hardcore punk scene. A collection of short, sharp bursts of adrenalised rock’n’roll delivered at breakneck speed, the record had many things in common with releases from the group’s contemporaries, and The Replacements’ performances were every bit as aggressive as those of the bands they cut their teeth playing line with. But, as Sorry Ma, Forgot To Take Out The Trash revealed, The Replacements had a secret weapon or two up their collective sleeve.

Listen to ‘Sorry Ma, Forgot To Take Out The Trash’ here.

Firstly, there was the melodic sensibilities and lyrical wit of frontman and main songwriter Paul Westerberg. Then there was the sheer musical fire-power at their disposal: guitarist Bob Stinson was a specialist in searingly inventive volatile solos; his little brother, Tommy, played bass with the sort of reckless abandon that only comes with youth; and drummer Chris Mars didn’t underpin the music so much as pick it up and pull it along with him. And where other bands of their ilk were worthy, The Replacements were charismatically joyful, offering a romantic and ramshackle alternative to the dour groups that made for much of the early 80s US punk scene.

“They had the raw power I’d been looking for”

As with so many other great bands, the story begins with a pair of brothers. Bob Stinson’s childhood had been extremely troubled: his parents separated when he was three years old, and his mother left Minnesota to start a new life in San Diego. Once settled, Bob and the family suffered for the best part of a decade at the hands of a sexually and physiologically abusive step-father until breaking free and returning to Minnesota in 1974. However, the damage was done for the 15-year-old Bob and, after a string of reckless drunken incidents, he entered a series of young offenders’ institutions before being discharged on 17 December 1977, his 18th birthday.

Throughout this period the guitar proved a lifeline, and Bob’s increasing proficiency on the instrument was identified by authorities as a potential saving grace. Meanwhile, Tommy was growing up fast. By the age of 12 he’d appeared in juvenile court three times on charges of theft, and Bob saw his brother heading down a familiar path. When Tommy showed an interest in a bass guitar at Bob’s place, the elder brother offered to teach him the basics, seeing it as an opportunity to straighten his younger sibling him out. Within months, Tommy was good enough for the two brothers and Bob’s roommate, Robert Flemal, to start a band, rehearsing all hours and playing backyard parties as a drummerless trio.

Things stepped up when drummer Chris Mars joined the fledgling group. The Keith Moon-worshipping sticksman had been bashing a kit since the age of ten and, when introduced to the Stinsons through a mutual friend, proved a natural fit. The four-piece, newly christened Dogbreath, threw themselves into local gigs, even adding Mars-penned original songs to setlists largely consisting of Yes and Peter Frampton covers. It wasn’t long before they caught the ear of local music obsessive Paul Westerberg.

“My plan was to learn the thing and wow them”

Westerberg also came from a troubled background. His father was a veteran of the Second World War and suffered from alcoholism while the young Paul struggled at school with learning difficulties. Music became a refuge and he immersed himself in The Beatles, Bob Dylan and Faces before moving on to Slade and The Rollings Stones and, eventually, falling for punk – particularly Ramones and Sex Pistols. At age 12, Westerberg bought a guitar for $10 from his sister and it became his constant companion as he practised alone. He’d later comment to Bob Mehr, author of the 2016 Replacements biography, Trouble Boys, “My plan was to learn the thing and pull it out one day and wow them.”

After making his talent public in his teens, Westerberg passed through a couple of bands, but always found them lacking in ambition. According to Westerberg, as he was walking home from work one day in Autumn 1979, he passed what he later realised was Bob Stinson’s place and heard Dogbreath rehearsing. He recalled to Mehr: “What got to me was the sheer volume and wild thunder. That was a major attraction: the balls of a band to play that goddamn loud.” He stayed to listen but couldn’t see who was making that glorious noise. A few months later, however, a mutual friend of Westerberg and Mars suggested the guitarist come to hear Dogbreath at rehearsal. As they pulled up to Bob’s house, Westerberg knew he’d found his band: “I knew that they had the raw power I’d been looking for… and that they might just be gullible enough to fall for me giving a little leadership,” he told Mehr.

Though they attacked their instruments with punk aggression, the music that had excited Westerberg wasn’t on Dogbreath’s radar. After bonding with the group and securing an agreement to jam together, Westerberg turned up at rehearsals with Johnny Thunders, New York Dolls and Buzzcocks records, encouraging a change of direction that was initially met with suspicion by Bob, who only came around to the idea after hearing The Damned’s 1979 album, Machine Gun Etiquette. The Replacements’ eventual line-up took a while to cement, but once various singers had passed through and Flemal eventually dropped out of the group, Westerberg took over on fantastically sloppy, sandpaper vocals, and the new-look outfit were on their way.

“It was bubblegum music sung by a guy who can’t sing”

Westerberg knuckled down to writing and, by summer 1980, had about 30 songs. They drew on his love of punk and garage rock but, crucially, also took their lead from the power-pop and singer-songwriter material that Westerberg also adored, which meant his songs were riddled with melodic hooks given a thrilling edge. He later reflected to Mehr: “It was bubblegum music sung by a guy who can’t sing… and they sort of harnessed that with their rock chops and made it better.”

It didn’t take long for The Replacements to make a reputation for themselves. The bandmates shared a predilection for alcohol-fuelled chaos, and early shows found them being dropped for bad behaviour, or virtually booed off stage for the state of their playing. Undeterred, Westerberg sharpened his writing, and the band recorded demos, eventually passing a tape to Peter Jesperson, local record-store owner and co-founder of Minneapolis indie label Twin/Tone Records. Jesperson was blown away by the energy of the songs and asked to see the band play as soon as possible.