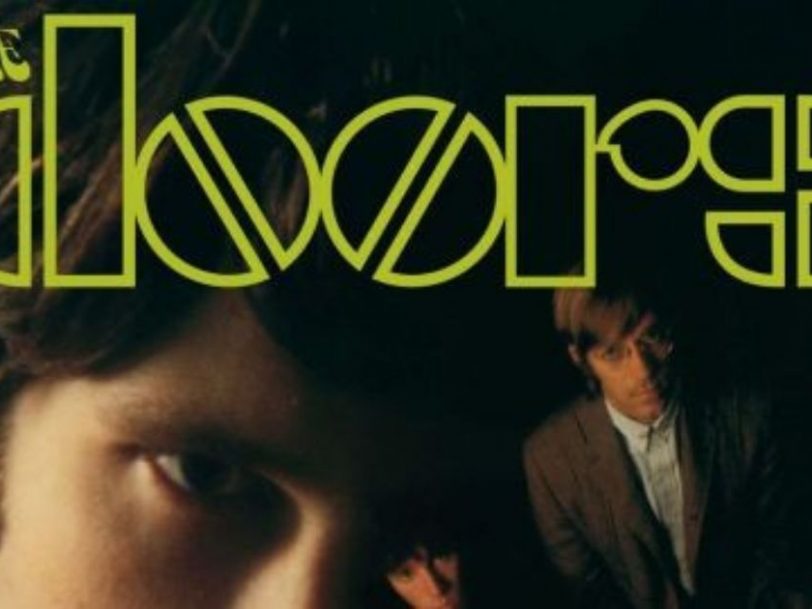

When The Doors’ self-titled debut album first arrived, at the start of 1967, US publication Crawdaddy described it as “an album of magnitude” before suggesting that the record was “as good as anything in rock”. It wasn’t the first album (and it certainly wouldn’t be the last) to be greeted with such fulsome praise, but, over half a century later, The Doors still stacks up to the hyperbole. Standing tall among the best debut albums of all time, it remains a touchstone of late-60s rock.

Listen to The Doors’ self-titled debut album here.

While it arrived sounding fully-formed and fabulous, The Doors’ debut album didn’t materialise out of nowhere. In their embryonic form, the band began after keyboardist Ray Manzarek first met novice vocalist (and UCLA film-school dropout) Jim Morrison in 1965, but The Doors’ classic line-up – with Manzarek and Morrison joined by guitarist Robby Krieger and drummer John Densmore – didn’t coalesce until the start of 1966. Even then, they were still unknown outside of their immediate circle when they embarked on their famous residency at Los Angeles’ London Fog nightclub in the spring of that year.

“They were kind of our heroes in LA”

It’s been well documented that this initial, dues-paying season of gigs – followed by a more high-profile residency at LA’s famous Whisky A Go Go – effectively set The Doors on the road to the superstar status they attained 12 months later. Certainly, the first half of 1966 was pivotal for the band’s development: by the time they were wowing audiences on a nightly basis at the Whisky, they had a killer set of songs and were fronted by a vocalist exuding star quality. The only question left unanswered was which record label they would sign with.

The hip Elektra imprint, co-founded in 1950 by Jac Holzman and Paul Rickolt, eventually won out, attracting the band thanks in part to its roster. “It was a small boutique label that had a bunch of artists that we respected, such as Paul Butterfield,” John Densmore told US publication Goldmine in 2017. “And Judy Collins was covering then-unknown Joni Mitchell and Leonard Cohen. It was just a very hip, small folk label, and we could actually talk directly to the president. It wasn’t a giant corporation.”

One of the label’s newest signings, Arthur Lee’s Love, also helped steer The Doors towards Holzman’s company. “They were kind of our heroes in LA,” Krieger told Goldmine, who figured that, if Elektra were “good enough for Love, they’re good enough for us. I always loved everything on the label. I probably had three quarters of their releases in my collection, so it was pretty cool to be on Elektra.”

“After months of playing nightly sets, we were able to go”

As it turned out, Elektra wasn’t just hip. Holzman and co really knew their business and, in producer Paul A Rothchild and engineer Bruce Botnick, they’d already lined up the ideal team to help bring The Doors’ debut album to fruition. The duo already had an impressive track record, with their credits including Paul Butterfield Blues Band’s first two albums.

“I had never met a producer or engineer before, really,” Krieger recalled in 2017, adding that Rothchild had worked on “a lot of” his favourite records. “It was amazing that we got him to be our producer… Paul was kind of a New York guy, and we didn’t know many people like that. He was this high-energy guy. He was very positive and super-hip. We immediately bonded with him. And Bruce was cool (and experienced), too. We were kind of in awe of those guys.”

The Doors were still lean and hungry when, on 19 August 1966, they entered LA’s Sunset Sound Recorders to begin work on their self-titled debut album, and the record was in the can after just six days of sessions. The band had honed most of the tracks to perfection during their endless slots at the London Fog and the Whisky, but the graft was worth it: rich, diverse and accomplished, The Doors was laden with classic material, and it felt like the work of a band with considerably more experience.