Released on the back of his commercial breakthrough, The Rise And Fall Of Ziggy Stardust And The Spiders From Mars, David Bowie’s sixth album, Aladdin Sane, rewarded him with his first UK No.1, introduced him to the US Top 20 and ensured his star remained very much in the ascendant.

Listen to Aladdin Sane here.

“Aladdin Sane was my idea of rock’n’roll America”

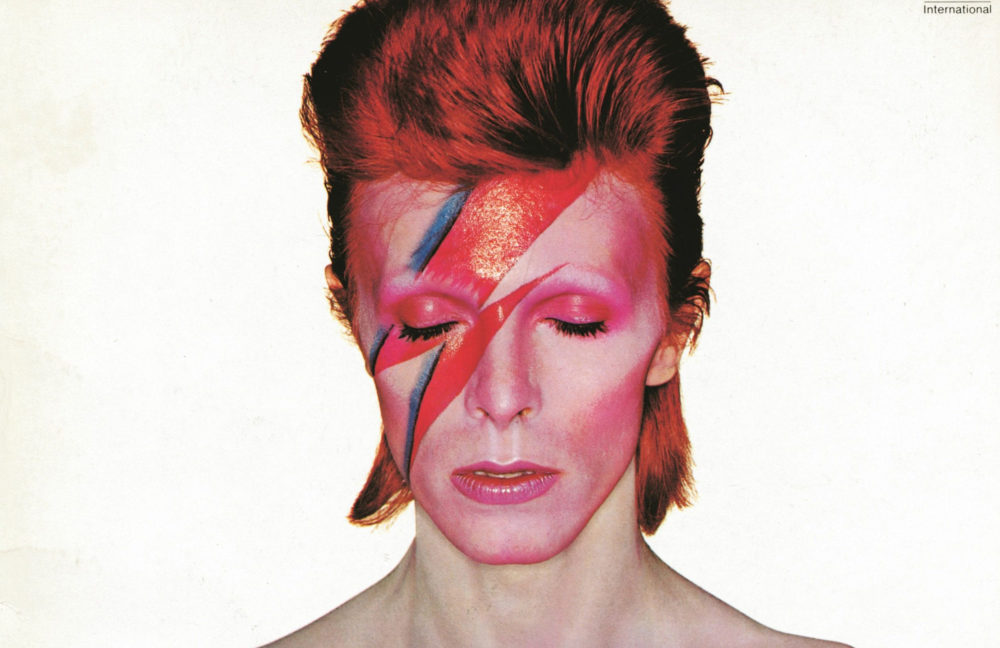

Initially viewed as an inferior follow-up to the stellar Ziggy Stardust, but now regarded as a landmark release, this adventurous April 1973 opus found Bowie adopting another new persona. Though broadly an extension of the messianic Ziggy Stardust, Aladdin Sane (a pun on the term “a lad insane”) was notably more dystopian in his outlook. According to Bowie biographer David Buckley, Aladdin Sane was a “schizoid amalgamation” – as reflected in Brian Duffy’s iconic album cover photo – one of the best David Bowie album covers of all time – in which a vivid red-and-blue lightning streak splits Bowie’s face in two, mirroring both his new persona and his contradictory feelings about his newly-acquired stardom in the US.

“Aladdin Sane was my idea of rock’n’roll America,” Bowie later reflected. “Here I was on this great tour circuit, not enjoying it very much. So inevitably my writing reflected that – this kind of schizophrenia that I was going through. Wanting to be up on stage performing my songs, but on the other hand not really wanting to be on those buses with all those strange people. Being basically a quiet person, it was hard to come to terms. So Aladdin Sane was split down the middle.”

“It’s a more successful album than Ziggy”

The US – in all its decadent, neon-lit glory – was writ large upon the album. Indeed, the panoramic scenery Bowie absorbed on the long Greyhound bus rides between shows on the Ziggy Stardust tour provoked him to write several of Aladdin Sane’s key tracks. The otherworldly desert landscapes of Arizona inspired the evocative, doo-wop ballad Drive-In-Saturday, while the album’s strutting lead single, The Jean Genie, first materialised during a journey from Cleveland, Ohio, to Memphis, Tennessee. During this lengthy drive, lead guitarist Mick Ronson hit upon a riff inspired by The Yardbirds’ take on Bo Diddley’s I’m A Man, and Bowie neatly married it to a lyric reputedly inspired by actress and Andy Warhol acolyte Cyrinda Fox (“Talking ’bout Monroe and walkin’ on snow white/New York’s a go-go and everything tastes right”), giving the song a chorus acquired through an imaginative marriage of Jean Genet’s name and Eddie Cochran’s 1958 single Jeanie Jeanie Jeanie.