Released two years after Country House helped them claim victory in the “Battle Of Britpop”, Blur’s self-titled album expanded the group’s scope beyond Old Blighty, as they decamped to Iceland for recording sessions and took in a transatlantic influence which would earn them significant success in the US. With it came a complete rethinking of what Blur could be at the end of the 90s, propelling them far beyond English whimsy and social commentary to ensure their continued relevance as the 20th century came to a close.

Listen to Blur’s self-titled album here.

“I wanted to scare people again”

With their fame-building trio of mid-90s albums, Modern Life Is Rubbish, Parklife and The Great Escape, Blur had cemented themselves as heroes of homegrown pop, pin-up cover stars for magazines from NME to Smash Hits, and purveyors of subversive chart hits which took a sardonic look at social mores while also placing the group right at the centre of contemporary British culture. By the time they came to record their fifth album, however, throughout the second half of 1996, they were exhausted by the media attention, bored with their tabloids-fuelled rivalry with Oasis and weighed down by the expectation of having to outdo themselves all over again. The solution: rebuild Blur from the ground up and challenge all assumptions of what the band were capable of.

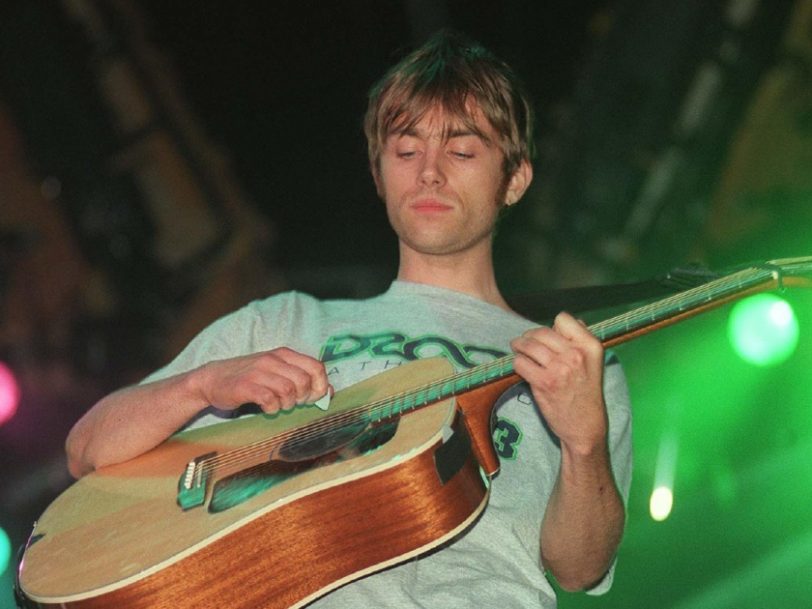

“I wrote Damon a letter just before we recorded Blur,” guitarist Graham Coxon later told music critic and Blur biographer Stuart Maconie, explaining the crossroads he felt the band had reached. “I said I wanted to scare people again… The letter worked.”

“I can write brilliant observational pop songs all day long, but you’ve got to move on”

Across their previous albums, the group had worked to an increasingly rigid framework, recording songs that frontman and chief songwriter Damon Albarn brought in, practically readymade before sessions had started. For their self-titled album, however, Blur began feeling their way through new material in the studio, working up songs together in a way they hadn’t since forming as Seymour in the late 80s. “It was the first time we sort of jammed,” Coxon later recalled, adding that the group were more accustomed to acting “quite white-coaty” during recording sessions, as though they were “in a laboratory”. This time around, however, the four bandmates would “actually feel our way through just playing whatever came to our minds and editing, which was really exciting”.

For Albarn, the change was welcome: “I can sit at my piano and write brilliant observational pop songs all day long, but you’ve got to move on,” he told Select magazine. After years of rejecting any notions of incorporating US influences into Blur’s sound, he began to take seriously Coxon’s insistence that Blur widen their sonic palette and look for inspiration in the culture that had once left them feeling homesick while touring their debut album, Leisure.

“I was always trying to mess around and be noisy and more exploratory with guitars because I was listening to the Americans,” Coxon reflected to Record Collector magazine, 15 years after the release of Blur’s self-titled album. Recalling his preference for using “guitars that had brittle sounds” on earlier songs such as The Great Escape’s He Thought Of Cars, the guitarist added: “English pop guitarists were pretty dull. I was always trying to get some Pavement or Sonic Youth thing going on.”