The fact we’re still discussing it almost 50 years later shows how seismic an event it was when David Bowie “retired” his Ziggy Stardust alter-ego and broke up his group The Spiders From Mars onstage at London’s Hammersmith Odeon in July 1973. However, in making such a grand gesture, Bowie was taking a significant risk. He had no master plan up his sleeve, so took a detour with the covers album Pin Ups while formulating what would become his next fully fledged studio album, Diamond Dogs.

Listen to Diamond Dogs here.

“He wasn’t quite sure what he wanted to do”

That Bowie hadn’t yet mapped his future out was apparent to insiders in his camp while he recorded Pin Ups. During these sessions in the late summer of 1973, guitarist Mick Ronson recalled, “David had all these little projects… but he wasn’t quite sure what he really wanted to do.”

The “projects” Ronson referred to included Bowie’s interest in adapting George Orwell’s influential 1949 novel, Nineteen Eighty-Four, into a rock musical, for which he began writing material before the Pin Ups sessions wrapped. However, while this putative idea was nixed when Orwell’s widow denied him the rights to the novel, Bowie ended up writing a concept album of sorts: an apocalyptic urban scenario influenced by Orwell, Anthony Burgess’ A Clockwork Orange and the works of another firm Bowie favourite, postmodern US author William S Burroughs.

“It was a precursor to the punk thing”

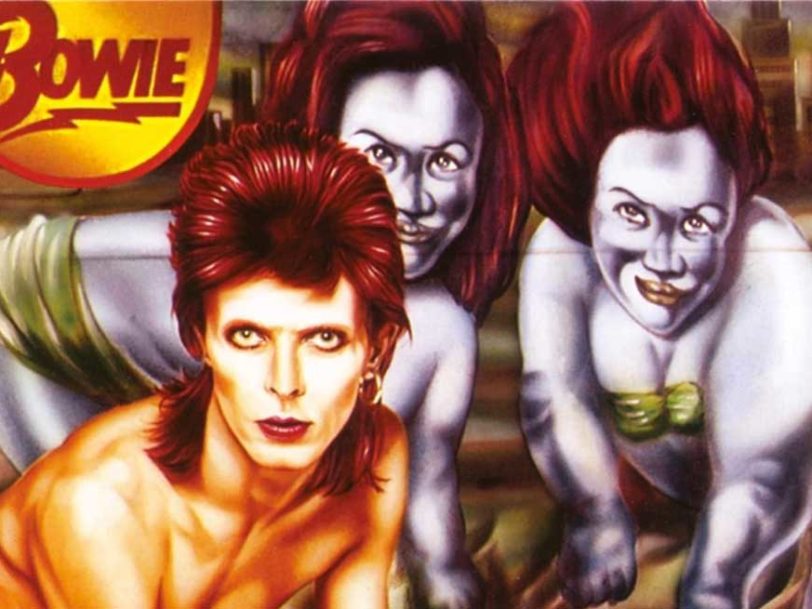

Accordingly, you could argue that Diamond Dogs was the logical extension of 1973’s Aladdin Sane, as many of its best songs delved ever deeper into that previous album’s dystopian themes. With hindsight, the record also envisioned the coming of punk – especially the pounding title track, which introduced Halloween Jack, a character whose decadent, shock-haired visage could have belonged to an alternate-reality version of Ziggy Stardust.