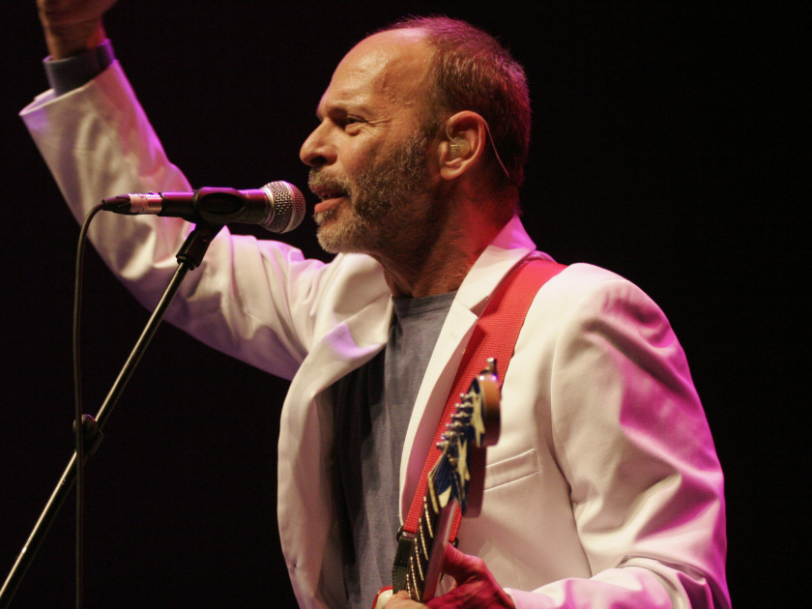

When MC5 guitarist and co-founder Wayne Kramer passed away, aged 75, on 2 February 2024, the rock world was quick to pay tribute to one of modern music’s genuine trailblazers. Iconic figures ranging from Alice Cooper through to Slash from Guns N’ Roses weighed in with well-chosen words, while in an especially heartfelt testimonial, Rage Against The Machine’s Tom Morello even said that Kramer and MC5 “basically invented punk rock music.”

On paper, that reads like one hell of a claim, but there’s plenty of evidence to support it. Famous for their radical politics, anti-establishment stance and their exhilarating, hard-driving rock’n’roll, MC5 were potent agents of change, whose music and attitude influenced the rise of punk in the 70s and inspired successive generations of independent, forward-thinking guitar bands – with Wayne Kramer arguably playing the most pivotal role in the band’s story.

Listen to the best MC5 songs here.

“The electric guitar was liberation – the sound of release and power”

Born Wayne Stanley Kambes, in Detroit, Michigan, on 30 April 1948, the future Wayne Kramer had a typically nomadic post-World War II upbringing. His parents divorced when he was young, and Kramer’s father, Stanley, effectively disappeared from his life. Raised by his mother and stepfather, the young Wayne sought solace in the seismic sounds of 50s rock’n’roll, with one pioneering figure in particular shaping the course of his future.

“Quite simply, Chuck Berry was the reason I played guitar,” Karmer enthused in the sleevenotes for Rhino’s The Big Bang! The Best Of The MC5. “When I heard that sound when I was nine years old, that was it. That was the sound of liberation, the sound of release and of power. And I mean the electric guitar. The sound of the amplifier was a huge part of it for me. That visceral sprit formed me and got me into bands.”

While in his early teens, Wayne found a fellow disciple in childhood neighbour and friend Fred Smith. Obsessed with their instruments, the two young guitarists played with a variety of local acts and sought out the hardest and most dynamic rock’n’roll records they could find (they took their cues from The Rolling Stones as well as Chuck Berry) before forming their own band, christened MC5. Short for “Motor City 5”, the name reflected urban Detroit’s primary industry – the manufacture of automobiles.

- Best MC5 Songs: 10 Classic Tracks That Kick Out The Jams

- Kick Out The Jams: How MC5 Booted The Door Down For Punk

- Back In The USA: How MC5 Invented Pop-Punk Ahead Of Schedule

“We liked the name. MC5 sounded like a car part,” Kramer wrote in his memoir, The Hard Stuff: Dope, Crime, The MC5 And My Life Of Impossibilities. “Give me one of those four-barrel carbs, a 4-56 rear end, four shock absorbers, and an MC5.”

By 1965, MC5’s classic line-up had solidified, with Kramer and Smith joined by bassist Michael Davis, drummer Dennis Tomich and vocalist Bobby Derminer. The latter was responsible for doling out more fitting stage names to his bandmates. Having rechristened himself Rob Tyner (after John Coltrane’s pianist McCoy Tyner), the afro-sporting singer invented Fred “Sonic” Smith for Smith, Dennis “Machine Gun” Thompson for Tomich and suggested Wayne adopt the surname “Kramer” instead of Kambes. Wayne did so, legally changing his name in 1965.

“Our fans were the blue-collar shop rats and factory kids”

During these early years, MC5 gigged constantly in and around the US Midwest. In the same way that punk later connected with the disenfranchised, the group established a solid fanbase among North America’s working-class communities.

“In Detroit, we ruled,” Kramer later asserted. “Our fans were the blue-collar shop rats and factory kids, and they connected with the energy and release in the MC5’s live shows. But our band was generally despised outside of the industrial Midwest power-base cities of Cleveland, Chicago and Cincinnati – and the hundreds of small towns across Michigan, Ohio and Indiana.”

Prior to signing with Elektra, MC5 released a couple of singles – the first a crunching cover of Them’s I Can Only Give You Everything, issued on AMG Records in 1967, with the follow-up pairing two self-penned songs, Borderline and Looking At You, for the small A-Squared imprint. However, while the records sold well locally, MC5’s attitude didn’t go down well with the era’s studio personnel – with Kramer in particular butting heads with the technicians attempting to tame the group’s sound for record.