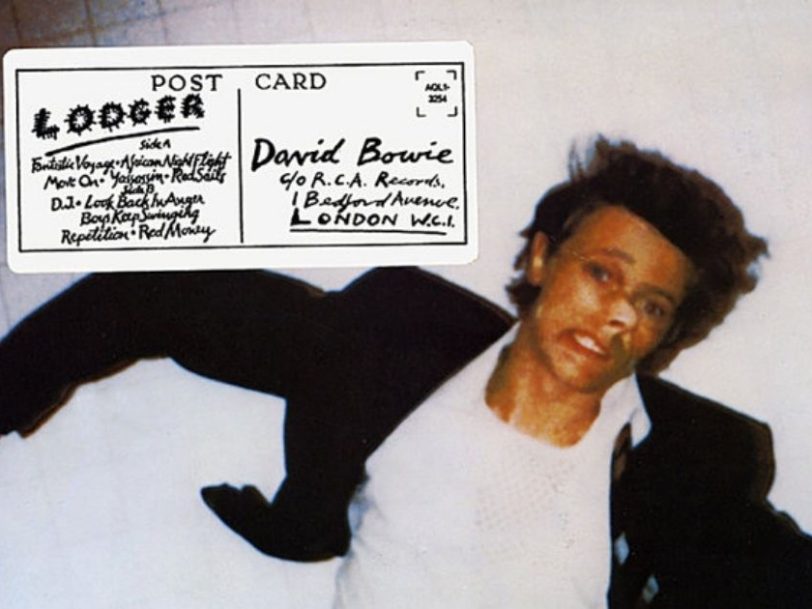

Released more than 18 months after “Heroes”, Lodger was seen as something of a late arrival in David Bowie’s “Berlin Trilogy”. Though not as bracingly revolutionary as that album – or it’s predecessor, Low, both of which had hit the shelves just seven months apart, in 1977 – its unconventional sound has, however, made for a subversive influence on purveyors of left-field pop. Tony Visconti, producer of all three records, feels Lodger features some of the best David Bowie songs he worked on. “Of the ‘trilogy’, this is probably my favourite,” he said, almost four decades on from Lodger’s original release. “I think the songs are amazing. They sound like Bowie classics and completely hide the fact that we were still experimenting.”

Listen to ‘Lodger’ here.

“‘Lodger’ is really a hodgepodge of styles that create a lovely mix”

Indeed, in the years following its release, the idea that Lodger has less to offer than its predecessors has become as fallible as its nominal placing within the “Berlin Trilogy”. Of the three Bowie records retrospectively grouped together under that banner, Lodger was the only one not to have been recorded, either in part or in full, in the German capital. Rather, on a break between legs on his Isolar II – The 1978 World Tour in September 1978, Bowie and his live band – plus Visconti and audio saboteur Brian Eno, both returning from the Low and “Heroes” sessions – settled into Mountain Studios, in Bowie’s recently adopted home of Montreux, in order to work on what would become his 13th studio album.

- ‘Lodger’ At 45: A Track-By Track Guide To Every Song On David Bowie’s Art-Pop Classic

- How David Bowie’s “I’m Gay” Interview Helped Redefine Sexuality

- Rebel Rebel: Behind The David Bowie Song That Kissed Goodbye To Glam Rock

Filling the longest gap between new records since Bowie released his self-titled 1969 album, the release of his narration of Prokofiev’s Peter And The Wolf had been an unlikely attempt to educate children about classical music, while the live double-album Stage offered a snapshot of the Isolar II shows as they’d rolled through the US earlier that spring. For his new album proper, however, Bowie sought to marry his avant-garde leanings with an increasingly cosmopolitan world view informed by influences he’d taken in while touring the globe.

“It was me trying to relate to that particular culture”

Though recorded with working titles such as “Planned Accidents” and “Despite Straight Lines” in mind, Lodger’s eventual title captured the peripatetic feel of much of the album’s music. Songs such as Yassassin took its name from “yaşasın”, the Turkish word for “long live”, and featured zigzagging violin lines that draped its funk-reggae backing in distinctly Middle Eastern dressing. Elsewhere, African Night Flight, in part inspired by a trip Bowie had recently taken to Kenya with his son, Duncan, rode the sort of African rhythms Brian Eno would further explore as a producer on Talking Heads’ albums Fear Of Music and Remain In Light, and on his David Byrne collaboration My Life In The Bush Of Ghosts. With Eno chanting a Swahili greeting and farewell – “Asanti habari habari ha/Asante nabana nabana na” – as if in answer to Bowie’s rapid-fire attempts “to get a word through one of these days”, African Night Flight, in particular, drew a direct line to Fear Of Music’s opening track, I Zimbra, and its collision of Dada poetry and Afrobeat-infused funk.