As far back as 1981’s Controversy album – whose title track placed a recitation of The Lord’s Prayer alongside the declaration, “People call me rude, I wish we all were nude/I wish there was no black and white, I wish there were no rules” – Prince had sought a way of uniting his sexual urges with his religious beliefs. As he perfected the “Minneapolis sound” on his breakthrough album, 1999, this became both more urgent and more clear: “I wanna fuck you so bad it hurts,” he pleaded on Let’s Pretend We’re Married, before asserting, “I’m in love with God, he’s the only way.” By the time he released the Lovesexy album in 1988, Prince had envisioned an entirely new state of being: the “lovesexy” of the title, in which sex could be as much a spiritual experience as it was a physical one.

Listen to ‘Lovesexy’ here.

“I did Lovesexy in seven weeks”

With Prince’s work rate at an all-time high in the late 80s, Lovesexy was recorded in under two months, from late December 1987 to February 1988, in Prince’s recently built Paisley Park complex. “I did Lovesexy in seven weeks from start to finish,” he later told Details, adding, “and most of it was recorded in the order it was on the record.” And yet it almost didn’t happen at all.

Initially intended for release that December was The Black Album: eight tracks, largely made up of raw funk with titles such as Le Grind and Superfunkycalifragisexy. Originally recorded on the fly for a birthday party thrown for drummer Sheila E, Prince quickly strung the songs together in a way that would have reasserted his funk credentials at the end of the decade he’d reigned over; recent albums Parade and Sign O’ The Times had been hailed as increasingly inventive creative highs, but some critics began to wonder if he’d left his Black audience behind. The Black Album – given a working title of “The Funk Bible” – would assure them he hadn’t.

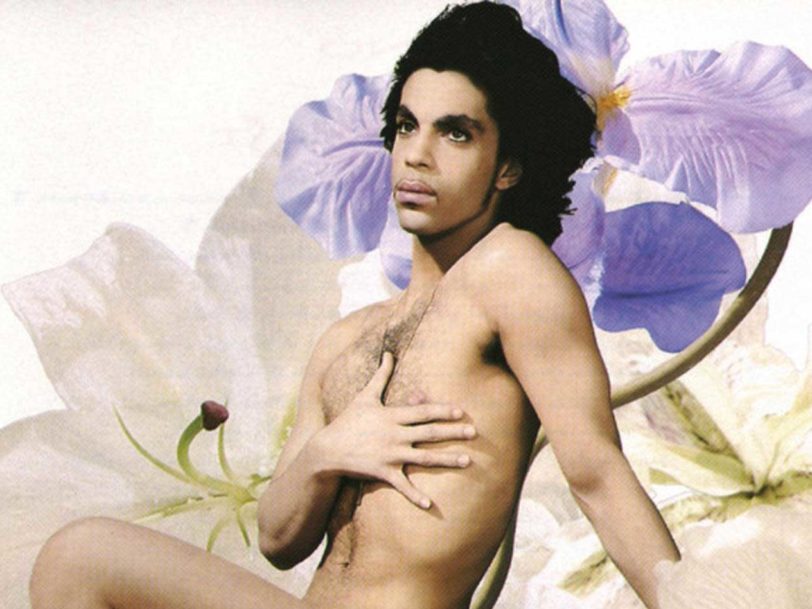

Housed in a plain black sleeve, with no artist credit or album title – just a peach catalogue number on the spine – The Black Album was sent out for promotion, and then pulled from release at the last minute. Prince never explained his decision, though word quickly circulated that, during a one-off experiment with ecstasy, he’d been spooked by a hallucination in which he saw the word “God” floating above him in a field. Now believing The Black Album’s forthright sexuality was evil, he scrapped it and immediately set about recording a more positive-minded work that would make room for lust and The Lord.