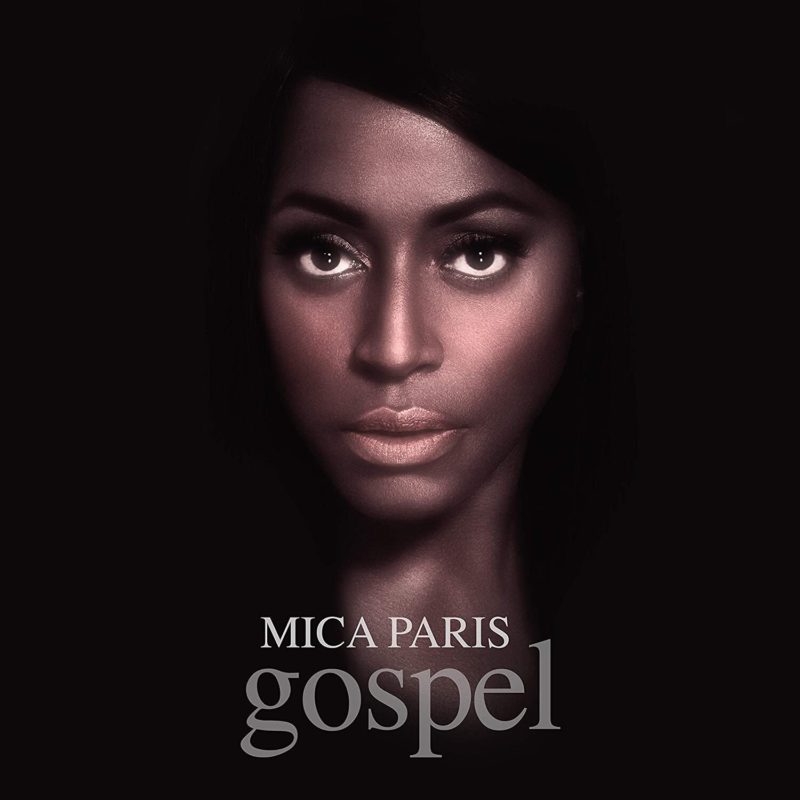

It’s not like Mica Paris to go quiet. Warm and effusive, she has maintained a decades-long career that straddles TV, radio and theatre – not to mention, in the 90s, a string of albums that gave the UK an R&B star who could hold her own against the US heavyweights. But fans of Mica Paris’ music have had to wait 11 years for her to finally break her silence on record, with the release of her new album, Gospel, on 4 December. Fittingly, the album is dedicated to the very people that gave the singer her tireless work ethic: her grandparents.

“It was drilled into me: make your own career”

“My family are the Windrush generation,” Mica Paris tells Dig! Travelling to England from Jamaica, they settled in Brockley, in the south-east of London. “I was raised by my grandparents” – Gwendoline and John Armstrong – “they were super proud; they were very studious. They didn’t play around.” Saving their money, “Mamma” and “Dadda”, as Paris called them, bought a five-bedroom house, providing a home for Paris’ Uncle Paul and Aunt Colleen, Mica’s two sisters, Dawn and Paula, and Mica herself – then going by her birth name, Michelle – the youngest of the three grandchildren. They were one of only two black families on their street. “It was drilled into me,” Paris says. “You never sign on. You must make your own career, your own money.”

That explains why, between the release of her 2009 album, Born Again, and her return with Gospel, Paris hasn’t really stopped. An acting role in EastEnders, as the no-fuss Ellie Nixon, currently brings her into UK homes four nights a week, while a wide range of theatre work – she has had roles in everything from The Vagina Monologues to Chicago – kept her on the stage throughout much of the 2010s. After a two-year stint with Fame wound up in 2019, in London’s West End, she could have been forgiven for taking a break. Instead, Paris found herself in the US, filming a TV documentary about gospel music.

“I finished Fame that October, and then in November I was on the plane with the crew,” Paris says. “We were flying around America, going to the plantation fields. I ended up going to Atlanta, Memphis – everywhere – to find out the history of Take My Hand, Oh Precious Lord, Amazing Grace.” But the BBC, who had commissioned the documentary, didn’t just want the history of the songs; they wanted Paris to tie her own life story in, too. Aired on BBC Four in July 2020, Gospel According To Mica: The Story Of Gospel Music “just kicked”. Paris says. “Everyone went mental about it.”