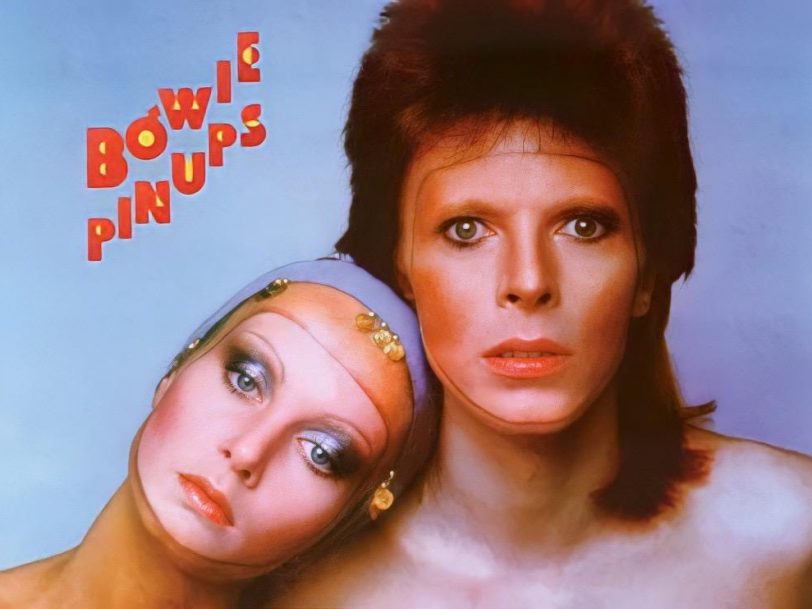

Adding the ideal final touch to the sonics contained within, the album came housed in a striking sleeve featuring an alluringly androgynous image of Bowie with the English model, Twiggy. A longtime fan, Bowie had previously paid homage to Twiggy by name-checking her on Aladdin Sane’s Drive-In Saturday (“She sighed like Twig the wonder kid”). As it turned out, the iconic model was more than happy to reciprocate by appearing with Bowie on the Pin Ups cover.

The legendary image – one of the finest David Bowie album covers – was thus captured by Twiggy’s manager and ex-boyfriend Justin De Villeneuve during the album sessions, with makeup provided by Pierre Laroche, whom Bowie had retained since his work on the Aladdin Sane artwork.

“The cover made perfect sense as Pin Ups was an homage to the 60s,” De Villeneuve said in a contemporaneous interview. “They were all David’s favourite records from ’64 to ’67, and Twiggy was the face of the 60s.”

“Glam rock’s most cogent expression of nostalgia”

Following a week after the single release of Bowie and co’s courtly version of The Merseys’ Sorrow, Pin Ups was released on both sides of the Atlantic on 19 October 1973, with advance sales of 150,000. An instant best-seller, it spent five weeks at No.1 in the UK, and its reputation as a fan favourite has long been set in stone (Bowie biographer Nicholas Pegg later suggested it was “perhaps glam rock’s most cogent expression of its own inherent nostalgia”). Its creator also retained a lifelong fondness for it.

“Pin Ups was really my way of shaking off Ziggy, while retaining some excitement in the music,” Bowie told Uncut in 2001. “It really was treading water in a way, but it also happens to be one of my favourite albums. I think there is some terrific stuff on it.”

‘Pin Ups’ Track-By-Track: A Guide To Every Song On The Album

Rosalyn

Bowie had previous with London garage-rock/psych outfit The Pretty Things before choosing to open Pin Ups with a cover of their debut single, Rosalyn. He’d seen the group plenty of times in London’s Marquee Club in the mid-60s, and had obliquely namechecked them in the Hunky Dory track Oh! You Pretty Things, in a game of lyrical cat-and-mouse that he would return to later in his career (1999’s ‘hours…’ album would feature a song called The Pretty Things Are Going To Hell). Pretty Things frontman Phil May later noted how faithfully Bowie stuck to the script with Rosalyn, simply choosing to supercharge their Bob Diddley-indebted R&B rave-up for the glam era and letting guitarist Mick Ronson loose on some careening slide guitar.

Here Comes The Night

Van Morrison sounds almost numbed by dark thoughts on the original Here Comes The Night, released by Irish rockers Them in 1964. Bowie, by contrast, launches into a full-throated wail from the off, and, drawing on the theatricality of his Ziggy-era stage shows, remains on high drama all through the choruses, dropping into a more measured, if no less stylised, register for the verses of a song about watching a former lover step out with a rival. Maintaining the heartbreak, Bowie finds space in the arrangement for a doleful saxophone solo that harks back to his days with his first band, The Konrads. “We were really pleased with that – we got a real Atlantic [Records] horn sound,” he told Sounds, two years ahead of going full-on soul boy on the Young Americans album.

I Wish You Would

Originally written by Chicago bluesman Billy Boy Arnold, I Wish You Would had featured in the repertoire of another of Bowie’s early groups, The Lower Third, who cut a demo of the song in the mid-60s. The song was also recorded and released by The Yardbirds in 1964, and it’s this faster version that Bowie looked to for Pin Ups, having violinist Michel Ripoche, from French prog band Zoo, double up on Mick Ronson’s pummelling riff before himself wading in on harmonica for his own brief tussle with the guitar. Things come to a halt via an explosive sound effect suggestive of the apocalyptic landscapes of Bowie’s Aladdin Sane album, or even his Pin Ups follow-up, Diamond Dogs.