The release: “As eclectic and puzzling album as Bowie’s ever made”

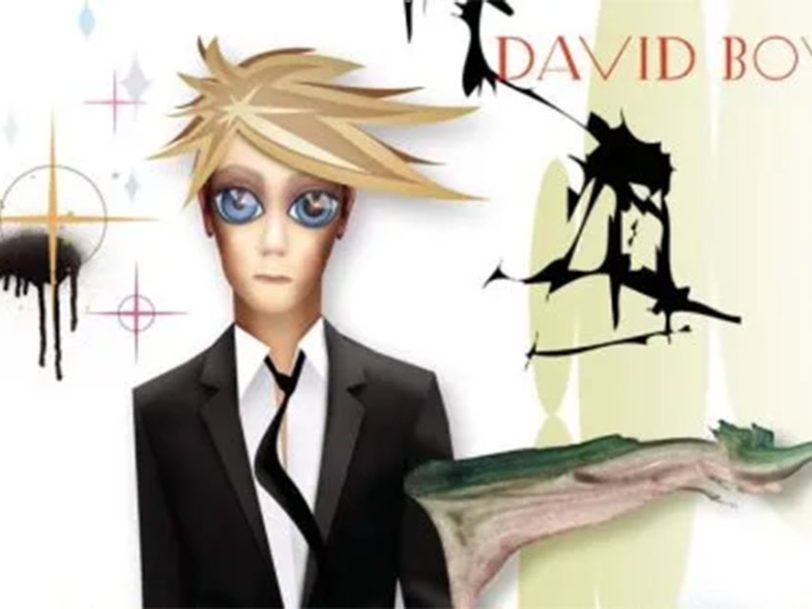

Released on 15 September 2003, Reality featured one of the most atypical David Bowie album covers: a design by Jonathan Barnbrook (Heathen, The Next Day, Blackstar) and illustrator Rex Ray (‘hours…’) which used Japanese anime as a jumping-off point for a portrait of Bowie, based on a Frank W Ockenfels III photo used inside the album’s packaging. “It’s the old chestnut: What is real and what isn’t? It’s actually about who’s stolen the world,” Ray said of the design five year’s after the album’s release. “The whole thing has a subtext of ‘I’m taking the piss, this is not supposed to be reality’,” Bowie himself clarified.

In reviewing the album, The New York Times observed how the recordings themselves seemed to bend reality, to the effect “that Mr Bowie and his spectacularly hard-rocking band might be about to materialise in your room”, while The Guardian praised the way Bowie mixed “classic – not nostalgic – rock” with “ambient duskiness and the electronic furbelows he has embraced since the 1990s”, before adding, “As for the ‘reality’ business, the lyrics leave you guessing.”

Noting the questions that coursed through the album’s 11 songs, Pitchfork called Reality “as eclectic and puzzling album as Bowie’s ever made”. But if Rolling Stone felt that Bowie’s search “for some version of truth” led him back to his prior conclusions that “truth is nothing but another mask… To his mixed dismay and amusement, meaning comes and goes,” Bowie himself countered that the search was ongoing.

“You know, in a few years my daughter is going to be asking, ‘Is there a God, Dad?’” he told Interview. “Am I going to be able to resolve that issue for myself before then? I don’t think so.” Elsewhere, he said, “It behooves me to find positivism in the way that I’m living more than anything else… I am actually searching for the optimistic in my life. And that’s generated by being a father again… Seeing in her eyes all the hope and optimism of the future, I have to reflect that somewhat in what I’m doing.”

The legacy: “There is something to be said for our future, and it will be a good future”

As Bowie prepared to launch his worldwide A Reality Tour – the longest of his career – the future promised great things. “We’re already half-talking about the next album,” he told Steinway, weeks ahead of opening the tour in Copenhagen on 7 October. “We leave an album always thinking, This is a good piece of work, and we judge it very much on the last day of when we’re listening to our final mixes. And at that point, it’s critical for us to look at each other and say, ‘This is a real success.’”

“He was in such a good place,” guitarist Earl Slick told Dylan Jones, for the book David Bowie: A Life. “On the road he had such a blast, smiling all the day, I’d never seen him happier.”