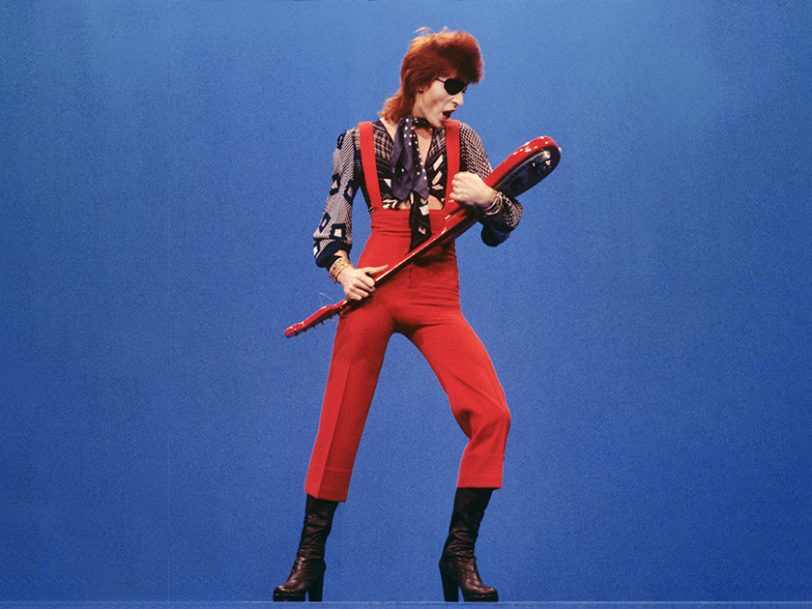

By the end of 1973, David Bowie was ready to leave glam rock behind. He’d already performed his final concert as his genre-defining alter ego, Ziggy Stardust, that summer, and, though still sporting his iconic red mullet and affording a last hurrah to an array of Ziggy-era costumes, he’d signposted a new direction for his music when he opened his US TV special The 1980 Floor Show with a funk-flecked new song, 1984. But before the year was out, the man who’d launched himself into the hearts and minds of his fans with Starman and penned a career-saving All The Young Dudes for Mott The Hoople had one more anthem for the glitter children: Rebel Rebel, a raunchy kiss-off to glam that, depending on where listeners were when they first heard it, also doubled as a slinky entrée to Bowie’s burgeoning romance with soul music.

The backstory: “I just want to piss Mick [Jagger] off a bit”

Having redefined the very concept of a live rock’n’roll show with his Ziggy Stardust tour, Bowie had begun to consider the natural next step for his increasingly ambitious performances: a full-scale musical-theatre production, complete with characters, storyline and stage sets. But while ideas for a pair of adaptations, of his The Rise And Fall Of Ziggy Stardust And The Spiders From Mars album and of George Orwell’s dystopian novel, 1984, remained unrealised, one song tentatively slated for the former project would ultimately find a spot on the album that grew out of the latter, as Rebel Rebel came to offer a moment of relief amid the apocalyptic visions of Bowie’s Diamond Dogs album.

The inspiration: “Your shoes are crap”

Many of the best David Bowie songs of the early 70s had foregrounded the gender fluidity that characterised the glam-rock movement. And just like Bowie had seemed to spotlight his fans on All The Young Dudes (“Now Lucy looks sweet ’cause he dresses like a queen”), with Rebel Rebel he spoke to his audience directly, intimately (“You’ve got your mother in a whirl/She’s not sure if you’re a boy or a girl”), flattering their flamboyance and their refusal to conform in their hunt for hedonistic abandon, while also letting them feel as though they were part of a unique group of fashionistas headed up by Bowie himself (“Hey, babe, your hair’s alright/Hey, babe, let’s go out tonight”).

Speaking to the audience at his VH1 Storytellers special, filmed in 1999, Bowie introduced his performance of Rebel Rebel with a recollection of his first meeting with future T. Rex mainman Marc Bolan, in the 60s. After an inauspicious start (Bolan to Bowie: “I’m King Mod. Your shoes are crap”), the two young hopefuls eager to find fame bonded while salvaging the faulty garments thrown out by the fashion retailers on London’s Carnaby Street. It wasn’t made explicit, but Bowie had intimated how the thrill he evoked in Rebel Rebel of being seen dressed to the nines on a night out (“We like dancing and we look divine”) was connected to those early years gleefully going “though all the dustbins around nine, ten o’clock at night” in order to “get our wardrobes together”.

The recording: “It’s a fabulous riff!”

To match the confident peacocking of the song’s revellers, Bowie came up with a guitar riff, part Marc Bolan, part Keith Richards, which strutted with street-smart savvy, as if the inner-city pavements were a catwalk cutting through the city. “It’s a fabulous riff!” Bowie later enthused of the simple, cyclical motif which underpins Rebel Rebel. “When I stumbled onto it, it was, ‘Oh, thank you!’”

Talking to Performing Songwriter in 2003, Bowie would describe it as the high-school-era riff “by which all of us young guitarists would prove ourselves in the local music store. It’s a real air-guitar thing, isn’t it?” Three decades earlier, he’d introduced it to Diamond Dogs session guitarist Alan Parker as “a bit Rolling Stonesy – I just want to piss Mick [Jagger] off a bit”. Having disbanded The Spiders From Mars that past summer, Bowie himself would play lead guitar on Diamond Dogs, and as he began to record Rebel Rebel at London’s Trident Studios, across three days beginning 27 December 1973, he and Parker finessed the guitar part that would provide the song’s through line. “He had it almost there, but not quite,” Parker told Uncut magazine, furthering elsewhere: “I said, ‘Well, what if we did this and that and made it sound more clangy and put some bends in it?’ And he said, ‘Yeah, I love that, that’s fine.’”

Finalised in the studio in early January 1974, Rebel Rebel would stand out from the more harrowing material that surrounded it on Diamond Dogs. As positioned on the album, it almost seemed to emerge gasping from the claustrophobic guitar, bass and drums coda that brought the Sweet Thing/Candidate/Sweet Thing (Reprise) medley to a close. But the clear, ringing mix picked for use on the album and achieved with the aid of Tony Visconti – returning to work with Bowie for the first time since producing 1970’s The Man Who Sold The World – was different to what fans heard when Rebel Rebel was issued as a single, two months ahead of Diamond Dogs’ release.

The release: “This is an anthem, let’s face it”

As released on 15 February 1974, with a kindred-spirit song, Hunky Dory’s Queen Bitch, as its B-side, the Rebel Rebel single edit ran ten seconds shorter than the album version and featured a noticeably different mix – one Bowie had completed himself, before taking the Diamonds Dogs tapes to Visconti. His vocals less aggressively to the fore, and with more space given over to Mike Garson’s piano, Bowie’s original mix of Rebel Rebel has something approaching an innocence the final album version cheerfully wrestles to the floor.

- The Real Reason Why David Bowie Had Different Coloured Eyes

- David Bowie Album Covers: All 28 Studio Album Artworks Ranked

- How David Bowie’s “I’m Gay” Interview Helped Redefine Sexuality

Having done enough to hit No.5 in the UK, where the last embers of glam rock were dying out, Rebel Rebel would receive another overhaul in time for its release in the US, where Kenny Gamble and Leon Huff’s Philadelphia International Records was reshaping the sound of soul music, and the popularity of the Latin soul of Fania Records was at its peak.

Arriving at New York City in April, Bowie and schoolfriend turned backing singer Geoff MacCormack took the Rebel Rebel tapes into a recording studio and, trimming over a minute from its running time, reworked the song into a tight dancefloor-filler that all but predicted the rise of the remix. Pulling back on the guitar riff that had ensured the song’s classic-rock status back home, the pair layered phased vocal effects, acoustic guitar, congas, guiro and other percussion which, far from playing up to the fads of the era, reconfigured Bowie’s last flirtation with the glam-rock sound he was leaving behind into something that hinted at the reinventions of his immediate future.

The legacy: “So many can relate to the rebellious spirit of this one”

When the Diamond Dogs Tour opened in the US that summer, the new-look Rebel Rebel provided the basis for a live arrangement that, now with added saxophone, upped the soul quotient of Bowie’s music, as Bowie transitioned into the “plastic soul” era of his Young Americans album. By the time he toured 1976’s Station To Station, Rebel Rebel had become a funk monster, and for the next decade or so the backing vocals Bowie and MacCormack added to the US in the spring of 1974 would be a key feature of the song’s live incarnations, right through to Bowie’s hits-focused Sound+Vision Tour of 1990.

Taking stock of his career in the early 90s, however, Bowie admitted to Q magazine that he’d begun to feel “uncomfortable” singing “generationally message-oriented” songs such as Rebel Rebel. Having been a fan-favourite for over a decade and a half, and a recognised highlight on one of the best David Bowie albums, Rebel Rebel seemed to be consigned to the history books as Bowie embarked on an astoundingly creative run in the 90s, during which he strayed even further from his rock roots. When he was ready to return to back-to-basics recording, however, Rebel Rebel was waiting for him, with the stripped-down arrangement unveiled during his ‘hours…’-era live shows providing the basis for a guitar-heavy re-recording included on the soundtrack to the 2003 action comedy Charlie’s Angels: Full Throttle. But it would be another remix opportunity that would bring Rebel Rebel up to date for Bowie in the early 21st century.

While promoting his 2003 album, Reality, Bowie approved a mash-up of Rebel Rebel with one of his new songs, Never Get Old, for use in an Audi car commercial. Seeking traction on the charts, a second mash-up was commissioned. Created by UK producer Mark Vidler, Rebel Never Gets Old breached the UK Top 50 in the summer of 2004. The remix was aptly named: 40 years on from its original release, Rebel Rebel had gone from being “a juvenile success” to a part of the cultural fabric, embraced by each new generation of music lovers.

So many can relate to the rebellious spirit of this one,” pianist Mike Garson observed of the song’s longevity, in 2020. “This is an anthem, let’s face it.”

Buy the 50th-anniversary ‘Diamond Dogs’ vinyl reissues.

More Like This

Vogue: The Story Behind Madonna’s Most Celebrated Video

As iconic as it gets, the promo video for Madonna’s Vogue single proved that the “Queen Of Pop” was all about making high art.

What’s Love Got To Do With It: Behind Tina Turner’s Universally Adored Anthem

A true 80s mega-hit, What’s Love Got To Do With It defined Tina Turner’s career, if not her outlook on life…

Be the first to know

Stay up-to-date with the latest music news, new releases, special offers and other discounts!