When Tin Machine initially emerged in 1988, David Bowie stressed that their formation had been an attempt to reconnect with “what used to excite me about being in a band”. Yet the critics of the day weren’t convinced. They preferred Bowie out front – the chameleonic star(man) living through (ch-ch) changes, not the besuited figure playing guitar-heavy rock’n’roll. Accordingly, many damned Tin Machine’s self-titled debut album and the arguably superior Tin Machine II with the faintest of praise.

With the benefit of hindsight, it now seems ironic that critics attacked Bowie for getting back to basics. After all, many of the same writers accused him of capitulating to the era’s glossier production values on his mid-80s titles Tonight and Never Let Me Down. Revisiting Tin Machine’s catalogue today, however, it’s clear that Bowie was actually as on-trend as ever. During this period, he regularly namechecked alt-rock acts he rated – among them Pixies and Sonic Youth – and both Tin Machine albums sounded bang up-to-date in an era when grunge was preparing to hijack the mainstream.

“I’m much more concerned with how I feel”

Not that Bowie was unduly worried about negative responses. “I’m sure there will be a lot of doubters, but it comes with the territory,” he told Rolling Stone when Tin Machine II was released in the autumn of 1991. “I’m a big boy and I find myself less and less interested with how I’m perceived anyway. I’m much more concerned these days with how I feel. I think the only way to work through all that confusion is to keep working.”

Bowie was as in-demand as ever in the late 80s and early 90s. In fact, Tin Machine had to take an enforced hiatus late in 1989 while he co-starred with Rosanna Arquette in the film The Linguini Incident, and then embarked on his massive Sound + Vision solo tour. A huge undertaking, the seven-month trek saw Bowie perform his greatest hits in five continents. However, even this high-profile extravaganza failed to diminish his enthusiasm for reconvening with Tin Machine.

“It was very exciting to work with those guys,” Bowie enthused in an April 1990 interview with Q magazine. “We decided when we formed that we’d play it from album to album, that if we were still getting on with each other – which was the priority – that we’d continue. So far it’s going great. If, after the next tour, we’re still enjoying the process, we’ll go in again and keep recording.”

“I remember being amazed”

Tin Machine did just that, nailing their second album during sessions in Los Angeles during the autumn of 1990 and spring 1991. Tim Palmer (Queen, U2) mostly took charge of production, though Hugh Padgham (Sting, Genesis) came in to work on one of the album’s best songs, One Shot. He later recalled the band were a highly talented unit – if somewhat chaotic in the studio.

“To the uninitiated, it could sound like a load of noise, but actually when you concentrated on listening, it made more sense,” Padgham told Bowie biographer David Buckley. “I remember being amazed by Hunt Sales’ [drumming] and I realised Reeves [Gabrels, guitar] was a master of his instrument in an Adrian Belew kind of way.”

In many ways, Tin Machine II was the logical successor to the band’s debut. Anthemic rock songs were still the order of the day, with the likes of You Can’t Talk and A Big Hurt driven by the door-slamming intensity of Sales’ drumming, while Gabrels joined the dots with his squalling guitars. However, the album also displayed a depth and refinement largely absent from its predecessor, with One Shot and Betty Wrong sporting confident harmonies and glorious choruses, and a muscular reworking of Roxy Music’s If There Is Something exuding just the right amount of panache to succeed.

Elsewhere, the band further upped the ante. They coated the slow-burning ballad Amlapura in all manner of Far Eastern spices and liberally imbued both Baby Universal (“Hello humans, can you feel me thinking?”) and the dense You Belong In Rock N’ Roll with Bowie’s otherworldly brilliance before signing off with the excellent Goodbye Mr Ed: a terrifically tense denouement in which Bowie’s gnomic free associations (“Never mind the Pistols/They laid the Golem eggs”) were whipped along by the push and pull of the music’s restless backdrop.

“It offers depth and texture… it’s often extraordinary”

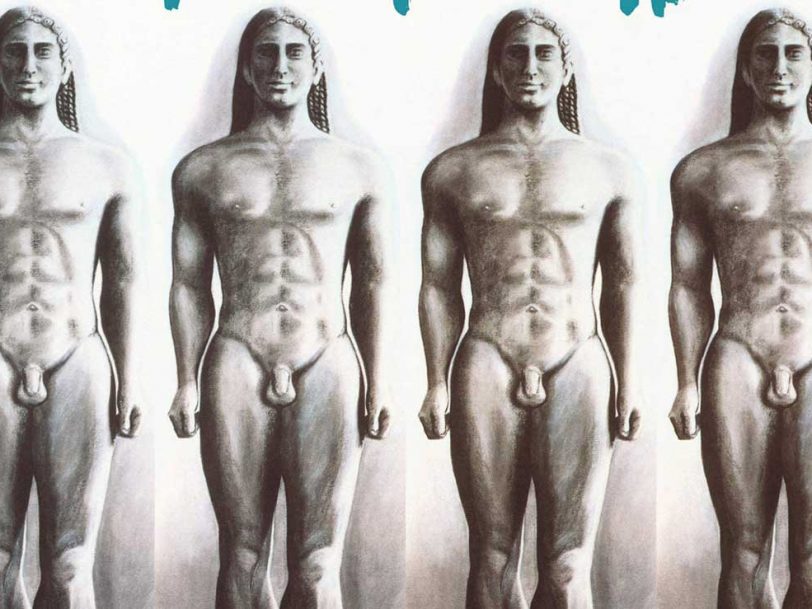

Housed in a striking sleeve depicting free-standing ancient Greek statues sketched by Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps) sleeve artist Edward Bell (a design that quickly became one of the most controversial David Bowie album covers), Tin Machine II was released on 2 September 1991 and performed more than respectably, peaking at No.23 in the UK charts and spawning a Top 40 hit courtesy of You Belong In Rock N’ Roll. Received wisdom generally relates that it was mauled in the press, yet, in reality, some of Tin Machine II’s reviews were extremely positive. The New York Times memorably described Gabrels’ expressive lead guitar work as “two parts Robert Fripp, one part Eddie Van Halen and one part speeding ambulance”, and Creem even declared the record represented “the best music Bowie’s released since 1980’s Scary Monsters”.

With Bowie deciding to return to his solo career with 1993’s Black Tie White Noise, Tin Machine were largely written off as something of a failed experiment. However, in more recent times, their music is finally gaining overdue recognition. Indeed, Tin Machine II appeared in Uncut’s 50 Great Lost Albums feature in 2015, and their ringing endorsement (“Overall, Tin Machine II was a better record than their debut, it offers depth and texture… it’s often extraordinary”) might just serve as the catalyst for the wider reappraisal both albums so richly deserve.