Tracy Chapman, the 1988 self-titled debut album by the US singer-songwriter, is much, much more radical than generally remembered. The phenomenal success of the album and its seminal lead single, Fast Car, has somehow blinded us to just how grave Chapman’s subject matter is, how biting her lyrics are; she is a Cassandra, speaking truth to a society that does not want to hear her.

Listen to Tracy Chapman’s self-titled debut album here.

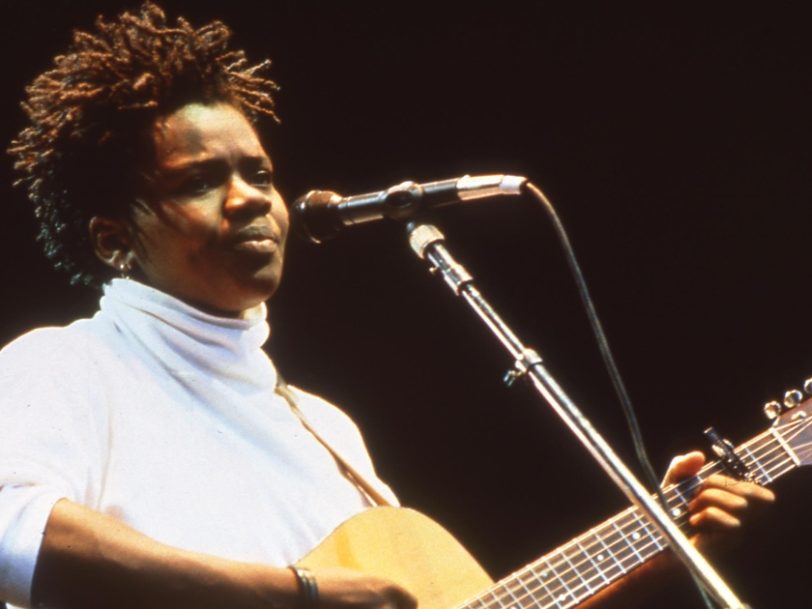

“There you have a picture of a very independent person”

Tracy Chapman was, in some ways, a very traditional troubadour. She was a young, socially-conscious woman and a fixture in coffeehouses in the town where she was studying (Danbury, Connecticut). Her debut album was an outgrowth from this period of her life – all of the songs on the album, with the exception of Fast Car, came from an early demo tape. She was “discovered” by another student, who introduced her to his father, the head of a publishing company. A deal with Elektra Records followed.

But that’s where the well-trodden routes stop. What Tracy Chapman did, on her self-titled debut album, was to fuse two distinct approaches, and her genius was to go beyond the niche. Instead, she looked outwards, embracing accessibility, and in doing so her music gave voice to millions, many of them marginalised because of race, gender, class or sexuality.