First released in July 1968, The Doors’ third album, Waiting For The Sun, topped the US charts for four weeks and eventually moved over seven million copies worldwide. Yet, while the record was an unqualified success, it also epitomised the notion of the “difficult third album”, with the LA-based quartet enduring gruelling studio sessions in order to get it over the line.

Listen to ‘Waiting For The Sun’ here.

“Jim would get really bored”

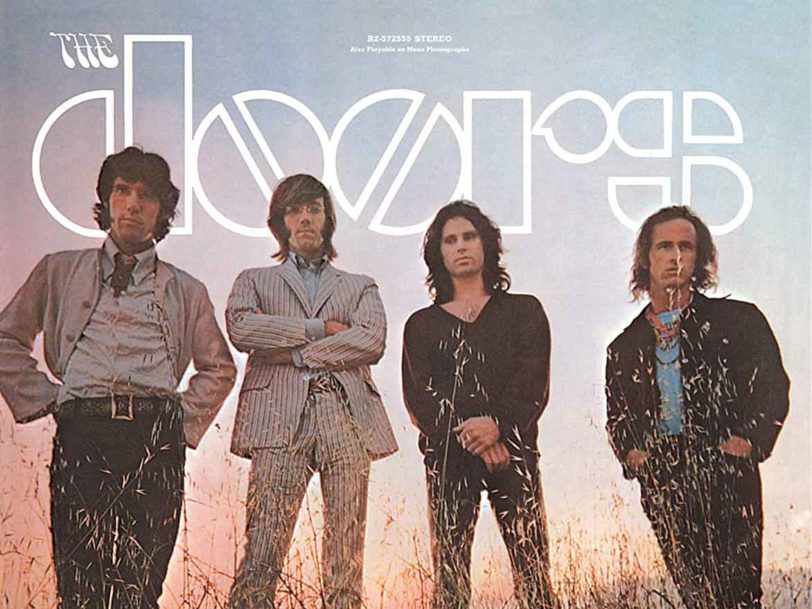

In a sense, The Doors had become victims of their own success. They’d enjoyed a phenomenal year in 1967, with their first US No.1 single, Light My Fire, and the releases of their self-titled debut album and its equally revered successor, Strange Days, transforming them into one of the world’s premier rock groups. Meanwhile, Jim Morrison’s natural charisma and photogenic looks ensured he was now very public property, but The Doors’ frontman also picked up an entourage of new friends demanding his attention – and his newly acquired taste for alcohol began to interfere with his artistic endeavours.

“By the time we got to Waiting For The Sun, we had enough money to spend a lot of time in the studio recording, so Jim would get really bored,” guitarist Robbie Krieger told Classic Rock in 2018. “We’d be spending six hours on the snare drum sound, and the vocal is always the last thing to be recorded. He would end up going to the bar and getting wasted, and was useless after that.”

Morrison’s apparently laissez-faire attitude to the sessions irked his bandmates, with drummer John Densmore even quitting the band – though he returned within 24 hours. However, other pressures also played their part, not least because The Doors embarked upon the sessions with a lack of new material at their disposal. The group had initially intended for their 18-minute epic, The Celebration Of The Lizard, to take up one side of Waiting For The Sun, but after several attempts to nail it failed, the band reluctantly started again from scratch.

“You’re kind of out of songs”

“We had enough songs for two albums before we ever went in to record the first album, but by the time the third album rolled around, you’re kind of out of songs,” Krieger reflected in a Billboard interview. “So I ended up writing more of the songs… I got to do stuff like Spanish Caravan and Yes, The River Knows.”